Introduction

You may think you know about Polaroid. It holds a special place for many of us. This unique, exciting, and immediate form of photography touched, if not every, most households in the United States at sometime in the second half of the twentieth century. And somehow when other films vanished in the wake of digital photography, Polaroid continued. When I encountered Beth D’Elia’s work, I was moved by the many ways she expands her Polaroids, revealing the possibilities that have been hidden inside the tidy little package the whole time. I hope you’ll enjoy our conversation.

Beth D’Elia is an experimental photographer based in Chicago. Beth blurs the line between photography and painting, working with Polaroid images to create whimsical, other-worldly emulsion lifts and manipulations. She uses water to transform hand-held images into unique works of art. With all things Polaroid—from the initial shot to finished product—her process is somewhat unpredictable. Take a moment to experience some of her work before reading our conversation.

Learn more about Beth’s work at: https://bethstinygallery.com

Our Conversation

Alexander: Thank you, Beth, for talking with me. I'd like to begin with your perspective. How do you describe your work?

Beth: I’m currently working with Polaroid and camera-less photography. Both produce results that are often unpredictable, surprising, even magical. I let the materiality of the film and photographic paper shine. My process is experimental. I soak, manipulate, deconstruct, and transform the Polaroid images in an intuitive process. I listen to the images. The results often blur the line between photography and painting. Likewise, with my camera-less work, I work in collaboration with light, time, and the photographic paper to create colorful mosaic and collage work. As with Polaroid, I’m interested in the raw materiality of the photographic papers and the colors produced. Much of my work is impermanent as it’s under a constant state of change.

Alexander: Your work with Polaroids is really exciting. I think a lot of people may feel like they have a really good idea of what a Polaroid is, what it does, what it looks like. This is probably related to both their experiences with and the marketing of Polaroids. You move past all of that and reveal a lot of surprising possibilities. You mention listening to the images. What is that like?

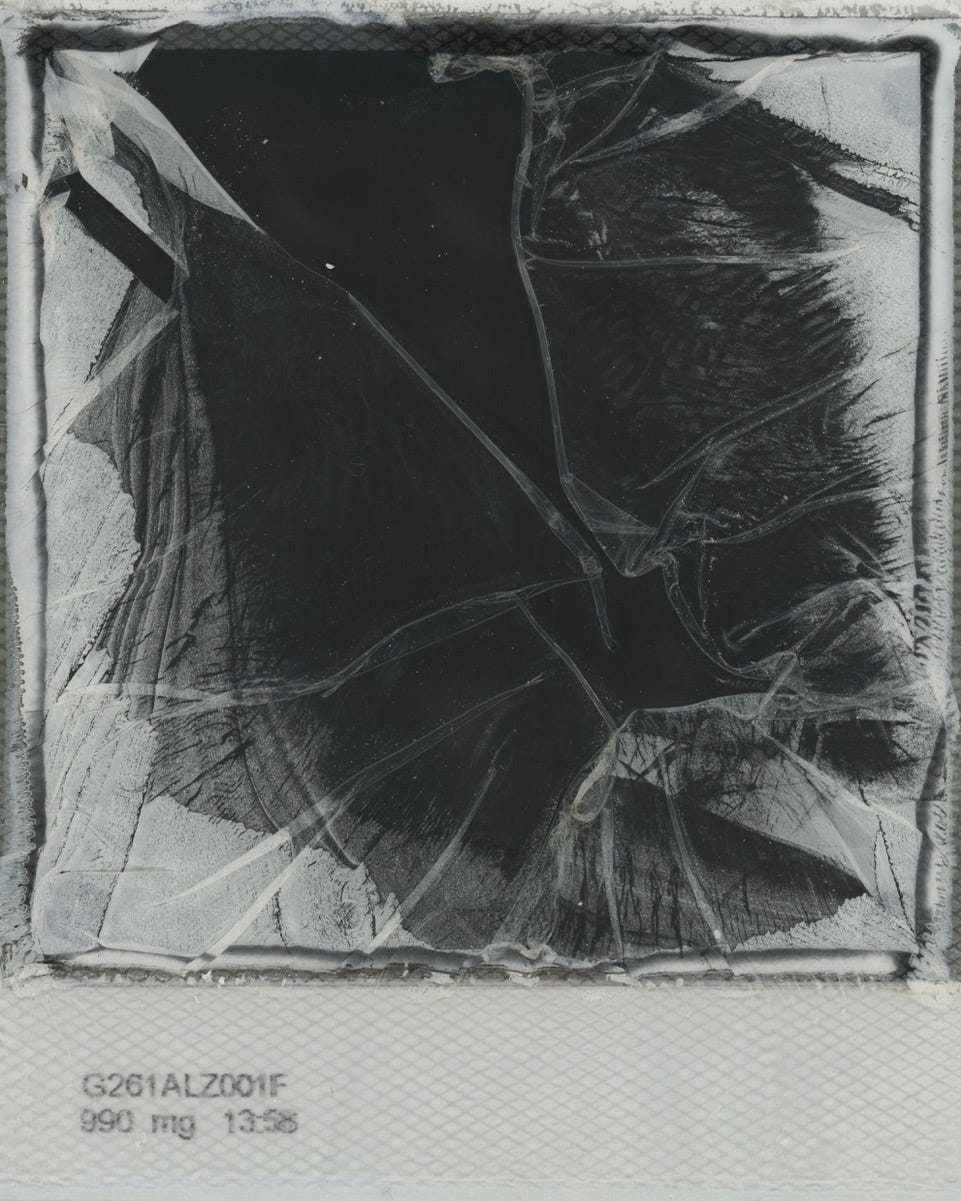

Let me talk about the image “Shattered.” I had dropped my beloved original SX-70 the week I made this image. I ended up loading some film into my SX-70 Sonar so I could continue with my daily “Dear Diary” project. The Sonar never really shot B/W Film very well but it was all I had at the time. This image was actually a failure (it ejected from the camera on its own without a shot) and coincidentally, I ended up dropping the Sonar camera too!

So, I intuitively ended up using this image to let out my frustration. I deconstructed it first by peeling off the frame. Then I opened the film up to create a transparency; the emulsion tore in the process. Next, I reconstructed it by putting the backing back on so you could see the black through. I called it “Shattered,” which is exactly what it became. It was a reflection of what I was feeling at the moment.

The great thing about Polaroid is that you have the positive and the negative in one package, so you can separate the backing from the front and manipulate the emulsion. I fell in love with Polaroid because of this. You can dive into it and create as you wish with the layers inside. My work slowly became not necessarily about the images themselves but how I express myself through the materiality of the film.

When I listen to the images, I listen to myself as well. Even while capturing a moment with the Polaroid camera, you never really know what the image is going to look like. I can have all the wants and visions in my mind, but the camera often does what it wants to do. I’m very comfortable working with the lack of control. I’m always excited to see what is produced after I press the shutter. The light, the weather, the environment all affect Polaroid film. Once I have the image in hand, I ask what this perfect square package wants to become. Sometimes the images are really good and they’re meant to stay as they are. Some have flaws that want to be explored further. Some are like paintings that beg to be transferred to paper. Often when I’m working on them, they do what they want. It’s almost like a collaboration. I make a move, the Polaroid responds, I respond back, and the process continues until I feel like the work is finished. The possibilities with Polaroid are endless.

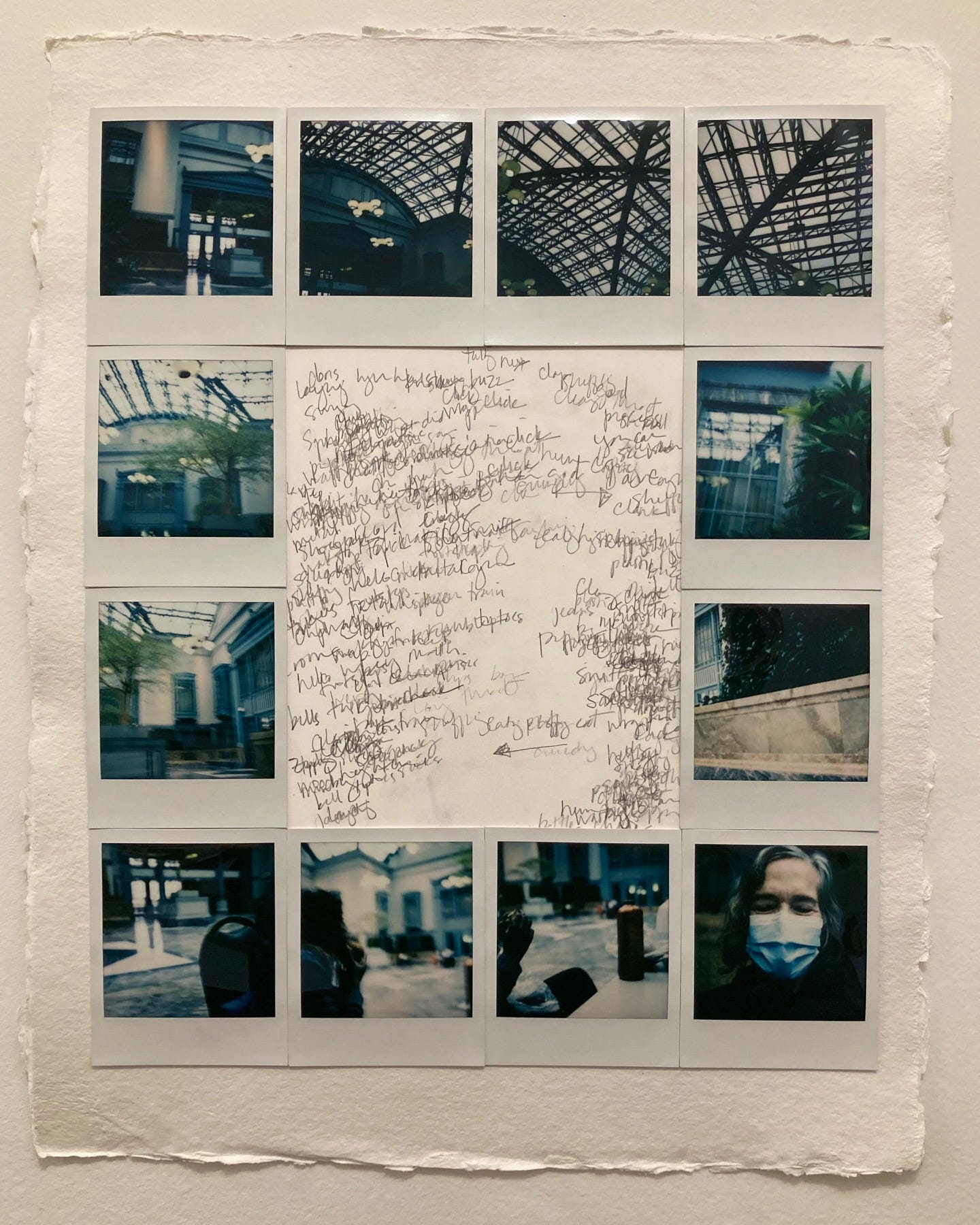

Alexander: Exploring the materiality of the film itself, collaborating with it makes a lot of sense. I'm also interested in this comfort with a lack of control. In your project, Ongoing Immersion Project: Eyes Closed . Ears Open you sit in a public space and close your eyes. You write down the sounds you hear in the space and take blind shots with the Polaroid SX-70 Sonar camera. I'm interested in how this approach developed.

Beth: I’m so glad you brought up that project. This project actually started as a response to a prompt of a listening exercise during a seminar in grad school. (I’m currently in the MFA Photography & Integrated Media program at Lesley University.) I decided to run with the project, take it outside to public gathering spaces, and use the SX-70 Sonar since its autofocus feature is based on sound waves.

It was an intuitive/immediate thought I had on how to respond to the initial prompt and I just went with it. It was definitely an idea put into action. I decided to take 16 blind shots (2 packs of film). I wanted to leave myself out of the process in a way. I wanted the camera’s sonar to pick up what it wished; I was leaving it up to chance. I really enjoy working this way, creating from a mess so to speak. I brought the images back to my studio and took some time with them and the notes that I took.

Initially, I created transparencies and was hiding my notes underneath, so you could see them but the images were taking the main stage. Then after I presented them at our jury critique, one professor suggested I pull the notes out from under the images as they play an important role in the works and deserve to be highlighted. I’m so grateful for his advice. I ended up reworking them all — I had five in the series at that point.

That’s the nice thing about Polaroid as well. They can be shifted around easily. On my sixth work in the series, the trajectory of the whole project changed. Someone sat with me and became part of the project. The project became performance based, and I then included a video component. So there has been an evolution in the process. This initial project has led to the development of two more projects that I’m currently working on. I haven’t published those yet, but I can give you a clue that I’m now taking portraits and have actually been incorporating some 35mm again — using my old Pentax K1000 from 25 years ago. I used to shoot street and portraits way back then, so it’s like my work is coming full circle.

Alexander: What it's like to return to 35mm film after 25 years?

Beth: It’s been a bumpy transition. I had to get the feel for my Pentax K1000 again. I was even fumbling around loading and unloading the film. It’s embarrassing how much I forgot. I actually ended up converting the first few portraits I did to Polaroid via the Polaroid Lab. The 35mm results hurt my eyes. The detail felt aggressive to me. But I’m slowly getting used to it and am now enjoying the bold colors and detail. I even tried working with a digital camera, thinking maybe I needed to go all the way into that realm. I hated it. Through that process, I discovered I really need to have that tactile feel of the older cameras. Which is no surprise, but I had to explore. I think I’ll end up using a mixture of Polaroid and 35mm for the project.

Alexander: For many people, photography is primarily a container for memory. What's the relationship between memory and your work?

Beth: I think I’m the opposite of most people. I don’t think about using photography as a container for memory. I don’t want to say that there is no relationship in my work. I do have some work that can be interpreted as memory, but it’s not something I consciously think about. My photography is more about illustrating a moment or creating something new. I don’t revisit the past much or use photography to hold onto the past. I’m more interested in possibilities and the power of photography to express something bigger — as a tool for illustration, telling a story, a narrative.

Alexander: Coming back to the importance of the tactile experience in your work. How does camera-less photography fit into your work and sense of collaboration with film?

Beth: I started using camera-less photography as a way to detach from the camera, to lose more control, to collaborate with the sun, time, elements, and photo paper. At first, I placed objects on the papers but found that the actual image wasn’t as important to me as the colors that appeared. So I got away from staging to just focusing on exposure time, light, and the elements outdoors to see what colors could be achieved. Then, I moved to placing the photo paper all over my apartment and in my studio so I could catch the ambient light. Without the interference of the elements outside, which can leave marks on the paper, I was creating pure sheets of raw color. I feel like this is the essence of photography, the simplicity of process, collaborating directly with the light and the paper.

I’m in a quandary with these works though because they have to be kept away in the dark because they’ll change with further exposure to light. I can fix them but fixing changes the colors — and I don’t want them to change. I’ve scanned some but I’m really in love with the papers themselves, they’re sculptural. I suppose these will (hopefully) be exhibited as impermanent works one day, changing throughout the exhibition, like a performance.

Alexander: As we've been talking, I've been thinking about your perspective on collaboration with the materials and with light and the different ways you take yourself out of the process, like with the Eyes Closed . Ears Open project. Is giving up control always easy for you? or is it ever a struggle?

Beth: Giving up control is really easy for me. It’s my preferred way of working. Adding an element of chance, taking risks. I’m kind of at a point and I think a lot of photographers may be at this point as well. We can take the picture. Everyone can take the picture now. We’re inundated with good pictures. So I enjoy throwing myself into photography in a different way at this stage in my life. I’m not looking for perfection anymore, and sometimes when I get that perfect shot, my impulse is to wreck it. Sometimes I try to be neat and orderly. In fact, I set out with these parameters for myself to fill a Polaroid album with 160 clean shots. I lasted 3 days, by the 4th, I had to tear into one.

I seem to always be looking for what I can create out of the mess I make. It’s thrilling to work like this. It’s invigorating. I like getting myself into trouble so to say and finding my way out and creating something new. It’s funny because I’m taking a painting class right now, and I work in the same manner. I look around in class and see everyone is so orderly with their colors. My station is a disaster zone. I’m mixing paints on the the canvas. On the palette. Not using the proper technique. And I’m sweating after I throw a random color on the canvas and freak out thinking, omg, what have I done? But, it all ends up coming together. I’m a fixer, I suppose. So, it’s very easy for me to not be in control.

It’s a struggle for me to be neat and orderly. Except for the grids and design. That’s where my precision comes in. But, I’m not one who uses a ruler. I eyeball everything. So, there you go … there’s even an element of chance, even within my precision.

Alexander: I admire your ability to be comfortable giving up control and approaching the materials, light, and time as collaborators. One of the things I'm really interested in when it comes to collaboration is the way individuals are changed through the process. Have the materials, light, or time changed you through your collaboration with them?

Beth: I would say that there’s a mindful quality to the way I work. When collaborating with things I don’t have control over, it slows me down. I take the time to listen, to think, to respond. There’s a meditative quality. I’ve become more aware, more connected to the present moment.

Alexander: Thank you, Beth for the opportunity to talk with you about your work.

Interview © 2023 The Root Cellar

All images © 2023 Beth D'Elia